Canada’s Monarchy throughout History

Every country has emerged out of a tangle of past histories, assorted land occupations by diverse peoples, climactic changes, colonization, the rise and fall of civilizations and an assortment of differing values. Every human being today stands on the shoulders and on the lands of those who have gone before.

Canada is no different, with its successive migrations from across the Bering Strait; quite possibly across the South Pacific and up from South America as well; and, centuries later, from the European continent. Historically, each new people brought with them their own complex society, whose ascendancy was in turn both displaced and absorbed by the next wave of newcomers.

Thanks to numerous discoveries by archaeologists and sociologists, we have come to understand that our Aboriginal ancestors knew both kingship—from Polynesia to the Americas—and a form of tribal leadership where local and some paramount chiefs occupied positions analogous to those of monarchs. Much later, the major European settler groups brought with them the ancient monarchies of France and of England, in whose name colonies were formed with their small populations gradually spreading across the land. Both these early and colonial monarchies frequently asserted that their authority derived from God, although this idea became extinguished over time.

Accordingly, some ancient Latin American kings, tribal chieftains of Aboriginal peoples and the sovereigns of France and Britain were absolute monarchs, holding to power by virtue of tradition, leadership and brute strength. In time, however, peaceful evolution in Britain and bloody revolution in France brought about change, whereby the principal political leadership fell to someone chosen by will of the people.

But many nations still valued the symbol of a constitutional monarch, above the partisan fray and a constant reminder to those elected that the power to govern was only lent and must be executed within the rule of law, which—along with basic values—were alive in the person of a hereditary sovereign.

Therefore, it is along with 14 other Commonwealth realms, and many other countries owing allegiance to different sovereigns, that Canada has constantly reaffirmed and maintained its constitutional monarchy since Confederation in 1867.

A List of Canada’s Sovereigns

The Canadian Crown

2022-

Charles III

1952-2022

Elizabeth II

1936-1952

George VI

1936

Edward VIII

1910-1936

George V

The English and British Crowns

1901-1910

Edward VII

1837-1901

Victoria

1830-1837

William IV

1820-1830

George IV

1760-1820

George III

1727-1760

George II

1714-1727

George I

1702-1714

Anne

1688-1702

William III

1688-1694

Mary II (jointly)

1685-1688

James II

1660-1685

Charles II

1649-1660

(Cromwellian Era)

1625-1649

Charles I

1603-1625

James I

1558-1603

Elizabeth I

1553-1558

Mary I

1547-1553

Edward VI

1509-1547

Henry VIII

1485-1509

Henry VII

The French Crown

1715-1775

Louis XV

1643-1715

Louis XIV

1610-1643

Louis XIII

1589-1610

Henri IV

1574-1589

Henri III

1560-1574

Charles IX

1559-1560

François II

1547-1559

Henri II

1515-1547

François I

The Monarchy and the Constitution

This is the subject of many books and articles, written for both specialized and general readers. The following article provides only a very brief and general outline of some of the major elements of a complex topic.

Canada’s Constitution, partly written and partly unwritten, consists of five elements:

The Monarchy in the Constitution Acts 1867-1982

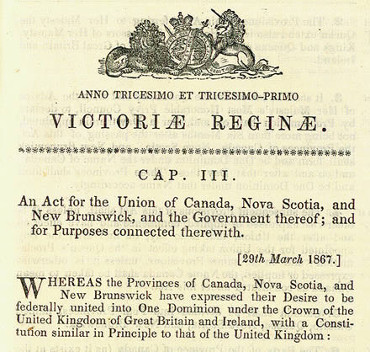

NB all references to “The Queen” refer to Victoria, Monarch of Canada at the time of Confederation, and are understood to refer equally to our past Kings as to King Charles III.

The Preamble states the desire of the original four provinces “to be federally united into one Dominion under the Crown of the United Kingdom and Ireland, with a Constitution similar in principle to that of the United Kingdom”.

Article 9 states “Executive Power of which and over Canada is hereby declared to continue and be vested in the Queen”. Article 10 goes on to refer to the Governor General “carrying on the Government of Canada on behalf and in the name of the Queen”.

Subsequent articles go on to constitute The Queen’s Privy Council for Canada—a committee of which forms the cabinet of the day—whose members are summoned and removed by the Governor General; to define the term “Governor General in Council” (so called “responsible government” whereby the Crown normally acts on the Advice of Cabinet); to vest the Command-in-Chief of military forces in The Queen.

Article 16 gives The Queen the power to move the capital from Ottawa—one of many powers our Sovereign is unlikely, but nonetheless able, to exercise!

Article 17 declares that the Parliament of Canada consists of the Queen, the Senate and the House of Commons. Article 24 allows the Governor General to summon Senators in the Queen’s name, and Article 26—used by the Mulroney government in 1990 to assure passage of the GST—permits the Governor General to recommend to The Queen the appointment of four or eight additional Senators beyond the usual composition of that body. Article 128 provides that all Senators, MP’s and legislative assembly members must take the Oath of Allegiance, the form of which is provided in The Fifth Schedule (an annex to the Constitution).

Article 38 provides that the Governor General in the Queen’s name summons the House of Commons to meet, while Article 50 declares the life of the Commons is five years “subject to be sooner dissolved by the Governor General”. Article 54 provides that a Royal Recommendation must be made before any money bill can be considered, and Articles 55-57 provide for the giving, withholding or reservation of Royal Assent by the Governor General in The Queen’s name before any bill passed by the Senate and Commons can become law, and the power of ultimate disallowance of legislation by the Sovereign.

Section V of the Act provides for lieutenant governors, appointed by the Governor- General-in-Council, to form the executive power within each province and, with the elected Assembly, to form the legislature of the province.

Section VII provides for the Governor General to name judges.

Section 41a of the Constitution Act 1982 provides that any constitutional amendment dealing “with the office of the Queen, the Governor General and the Lieutenant Governor of a province” must be passed by resolutions of the Senate, the House of Commons and all 10 provincial legislatures. The safeguarding of the Crown in this section is called “entrenchment”, meaning that any change to such a fundamental aspect of the constitution is deliberately made very difficult to achieve.

The British North America Act, 1867

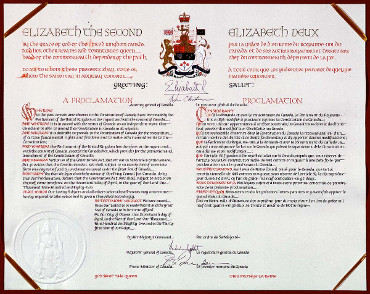

The Constitution Act, 1982

The Royal Victorian Order

The Queen and the Rt Hon. Stephen Harper

The Royal Prerogative

The Royal Prerogative refers to the powers naturally retained by the Sovereign, or given by law to him. It is what remains of the near-absolute powers once possessed by medieval monarchs. However, as we live in a constitutional monarchy, the Royal Prerogative has subsequently been diminished with the development of modern democracy.

The essence of the Canadian state—and most modern states—is responsible government; that we are governed from day-to-day by those whom we have elected; and that the Sovereign and her representatives must normally act on substantive matters only on “advice”—that is, if the prime minister recommends that Parliament be dissolved, or that legislation receive Royal Assent, or that Mary May Simon be named Governor General. It would be an extraordinary circumstance if the Sovereign or Governor General were to to refuse such “advice”, conceivable only were the prime minister enmeshed in scandal or lacking the confidence of the House of Commons. In short, the monarch reigns, but does not rule.

Many of such Royal powers are defined constitutionally and legislatively; for instance, The King’s ability to summon and dissolve Parliament, to name a governor general, to name additional Senators. Strictly speaking, these are not “pure” instances of the Prerogative. For as mentioned above, they would normally be exercised on “advice of an elected government”.

However, two areas exist where the purest form of the Royal Prerogative remains intact, one quite common and uncontroversial, the other that is usually only the subject of speculative debate. In its common form, The King or his representatives can award honours that do not fall within the ambit of constitutional “advice”, such as the Royal Victorian Order in the case of The King, or the Vice-Regal Commendation in the case of his representatives. His Majesty can choose whether to approve the use of the Royal Crown in heraldic grants; the organizations to which he will accord the prefix “Royal” or grant his Patronage; the use and design of her image on stamps, coinage and bank notes; the details of new honours and decorations and medals. These are important symbolic details in the life of the nation. As well, The King or his representatives have the right to encourage, to warn and to be advised by the government of the day. Influence and experience are often as potent as sheer partisan advantage. Having access to facts is also a form of subtle influence. In this way the monarch, his representatives, reflect their concern for the general good, and act as a valuable and absolutely confidential sounding board for prime ministers and premiers.

Another form of the routine but important use of the Prerogative lies in the constitution of the office of Governor General. While the position is mentioned in a matter of fact way in the Constitution Acts, it does not define the Office. This is remedied by an exercise of the Prerogative, whereby the Sovereign (initially, George V in 1931, then George VI in 1947) created the position and laid down instructions for its occupant, in a document entitled Letters Patent Constituting the Office of Governor General of Canada.

Section II grants the Governor General the exercise of “all powers and authorities” of the Sovereign, while section XII codifies the Prerogative Power of Mercy—pardons and remissions of sentences. Section XV is particularly important, as it reserves to the Monarch the right to “revoke, alter or amend” the Letters Patent at any time; in other words, the Prerogative is not touched by the delegation of royal power to the Governor General, nor is there any restriction whatsoever on the monarch exercising personally any of those royal powers.

In its exceptional form, The King can act as a “constitutional fire extinguisher” should normal democratic processes break down. This could occur if a Prime Minister lost the confidence of the House of Commons but refused to resign—the Prerogative power could be used to dismiss him and to make sure that the democratic will of the electorate would quickly have an opportunity to make its voice heard. Should a disaster decimate the government, it is the Crown that would have to reconstitute a legal administration and make sure the machinery of the state were directed in time of crisis—again with the understanding that at the first opportunity, normal democratic processes would be restored.

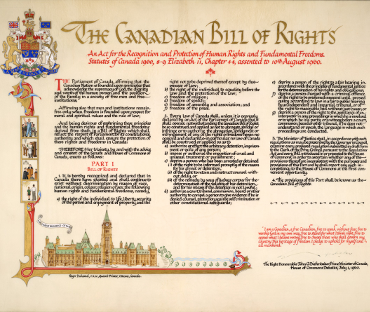

Organic Laws

Scholars often consider certain statutes to be so fundamental to the nation that they are quasi-constitutional documents. The Supreme Court Act is one such statute; The Canadian Bill of Rights, passed by Parliament in 1960, is another—it contains some provisions not included in the Charter which it pre-dated by nearly a quarter-century, and is still cited in court decisions.

Paramount amongst organic laws, however, is the Statute of Westminster (1931). Its principal purpose was to provide for legislative independence for the then-Dominions of the British Empire. For Canada, this meant that aside from giving effect to certain constitutional amendments, the British Parliament could not longer legislate with respect to Canada, except upon an explicit request to do so. The last such request came with the passage of the Canada Act, 1982, whereby the final elements of Canada’s Constitution were patriated—made amendable entirely in Canada by Canadians. In addition, the Statute sets out the convention that any change in the succession to the Throne would require unanimous consent of the Commonwealth Realms—the countries which share a monarch with the UK. This has continuing implications as those countries consider whether primogeniture—inheritance by the eldest son—and the disability of Roman Catholics to inherit the Throne—should continue to govern succession.

The most important organic law in recent years is The Succession to the Throne Act 2013 which was passed unanimously by both Houses of Parliament. Confirming contemporary Canadian values in line with the other Commonwealth Realms and the approval of The King, it achieves two main purposes. The first is to eliminate gender discrimination in the Succession. Henceforth, men and women will take their place in the Line of Succession in order of birth, rather than males having precedence – a preference sometimes referred to as primogeniture. Thus, for example, the Princess Royal (Anne) and her children and grandchildren would take priority over her younger brother, Edward (Earl of Wessex) and their descendants. The second chief purpose of the Act is the elimination of the unique proscription against the Heir to the Throne marrying a Roman Catholic, an accomplishment of particular significance to Canada and Canadians of whom about 40% are Catholics. Hitherto the Heir could marry a Hindu, a Jewish person, a Muslim – even an atheist – but not a Catholic.

The Canadian Bill of Rights, 1960

The Supreme Court of Canada

Court Rulings

Especially in the early days of Confederation, and again in recent times subsequent to the entrenchment of The Charter of Rights and Freedoms in Canada’s Constitution, the courts have been called on to rule on matters so fundamental that some of their decisions effectively make law, and form part of the constitution.

An early example of this process is seen in Liquidators of the Maritime Bank v The Receiver-General of New Brunswick, the effect of which was explicitly confirmed by the the Supreme Court in The Attorney General (Canada) vs The Attorney General of the Province of Ontario (1894) stating the former case “definitively established that a Provincial Lieutenant Governor appointed by the Governor General…represents the Queen”, using the oft-quoted words, “The Lieutenant Governor of a province is as much the representative of Her Majesty the Queen for all purposes of provincial Government as the Governor General himself is for all purposes of the Dominion Government”. This served to enhance the status of lieutenant governors and, needless to say, made more potent the claims of sovereign power exercised by the provinces within Canada’s federal system.

A more recent ruling came in 2008 with the opinion of of the Federal Court of Canada. In Giolla Chainnigh v Canada (Attorney General), it was made clear who is Canada’s head of state, writing:

I cannot think of any Canadian institution where an expectation of loyalty and respect for the Queen would be more important than the Canadian Forces. Whether Capt. Mac Giolla Chainnigh likes it or not, the fact is that the Queen is his Commander-in-Chief and Canada’s Head of State. A refusal to display loyalty and respect to the Queen where required by Canadian Forces’ policy would not only be an expression of profound disrespect and rudeness but it would also represent an unwillingness to adhere to hierarchical and lawful command structures that are fundamental to good discipline.

Chainnigh had claimed he had suffered “institutional harassment” by having to show respect and loyalty to The Queen as an officer in the Canadian Forces. The Federal Court ruled against him. Similar cases arguing the Oath of Citizenship being an Oath to the Sovereign have in recent years been heard and rejected by the Courts. Extensive coverage of some of these cases including judicial decisions, is provided in the League’s publication, Canadian Monarchist News, all of which are available through the League’s online Archives

Constitutional Convention

The heart of the unwritten part of the Constitution lies in tradition, which is effective only by common agreement and civility rather than law. Nonetheless, custom and convention are extremely potent actors on the constitutional stage. You will search in vain in the statue books for any reference to the most fundamental principal of Canada’s democratic parliamentary institutions, that the government must maintain the confidence of the House of Commons, or resign.

From a close reading of the Constitution, you might also imagine The King as a dictator who alone summons and dissolves Parliament, concludes treaties, declares war, situates the national capital, appoints his Governor General and withholds approval of any legislation he does not like. And you might well wonder how the Statute of Westminster, an act of the old Imperial Parliament, can bind independent members of the Commonwealth to agree on the succession to the Throne.

Actually, the fact that significant elements of our Constitution rely on good-will “custom and convention” in legal terms—is not so strange as first it might seem, even in this modern era with its penchant for exactness and definition of many matters. No law has ever created the institution of the family, or compelled that parental love which lies at the basis of happiness. There is no Act of Parliament which makes anyone give up his seat in the bus to a burdened senior citizen, or to shake hands when introduced to someone; to say thank you to a waiter or to bring mother breakfast in bed on her birthday; to stand to respectful attention as the National Anthem is played or to apologize for trampling a neighbour’s garden. Yet these little courtesies, and a thousand others like them, weave the basis of civil society.

So it is with the constitution of countries who have inherited from Britain the notion that not everything can or should be written in a law book, nor can every exigency of national life be provided for. Flexibility and good will, respect for the customs of the country, fair play and common understanding help to guide the affairs of the realm as much as the relationships between human beings.

Therefore, The King, the embodiment of the country and source of all authority, is in the final analysis but another human being. This is congenial to most Canadians, who recognize that the deepest loyalties of men and women are not to abstractions, nor to political documents, nor to government, but to other humans. It is then entirely appropriate that a constitutional monarchy such as Canada depends on the human factors of convention and custom as the underpinnings of its constitution. Reigned over by an admired King, the nation famed for humanity and tolerance puts its ultimate faith in its people.

Elizabeth II proclaims the Constitution Act 1982